Just like g̱a̱boox [g̱a̱/*boox] – cockles, you can harvest ts’a̱’a̱x [ts’a̱’a̱x] – clam (common noun) throughout the cold winter months. Ts’a̱’a̱x live low in the intertidal zone, but above the g̱a̱boox (they live even lower down in the intertidal zone). Shellfish, including ts’a̱’a̱x and g̱a̱boox, can be harvested about twice per month on the low-low tides (the new moon and the full moon). In the winter, these tides are often during the night, which is why you’ll see people going out clam and cockle digging when it’s dark. Once in a while, there will be a suitable tide during the day – which we like to take advantage of!

Clams are bivalves, meaning the way that they eat is by sucking in ocean water through their siphon and consuming the organic foods that wash over ocean beaches.

Harvesters are always conscientious of the presence of biotoxins in bivalves, such as clams, cockles, and mussels, which can cause shellfish poisoning. The most common/severe shellfish poisoning that people worry about is paralytic shellfish poisoning (or PSP), but there are two other types of shellfish poisoning that have been documented in Canada: amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP) and diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP).

The way that shellfish, specifically bivalves, accumulate toxins involves the food they eat is how they digest it. The risk of biotoxins becomes more prevalent during the warmer months – when the sun and warm weather cause variety of chemical and biological reactions in the ocean. Algae is a microscopic ocean plant that requires light and heat to photo synthesize. The sudden warmth and sunshine in the spring tells the algae particles to start their bloom. Algae blooms are a natural occurrence, but they can also be the cause of harmful algae blooms – including red tide. In this scenario, a red tide will drop the oxygen in the ocean – killing plant and animal life alike – not to mention being harmful to humans! A single red tide can last from a few days, to a few weeks. Once the algae is finished blooming and starts to die, it releases toxins into the water. Bivalves, such as clams, eat that toxin through their siphon, which starts the process of bioaccumulation in the clam. The clams’ toxicity level fluctuates throughout their year, but toxins usually drop by Ha’lila̱x sits’a̱’a̱x [ha/’li/*la̱x/si/*ts’a̱’a̱x] – the time to harvest clams, November.

In our area, First Nations fisheries/stewardship groups with territory on the coast often do shellfish sampling in their traditional territories, to ensure biotoxin levels are below a certain threshold. Before going out harvesting, it’s always good to check out your communities website and social media pages before you go out to harvest in those areas. Down south on Vancouver Island, DFO does sampling to open recreational clam fisheries for everyone – but not so much in this area. Here in laxyuubm Ts’msyen (Tsimshian territory), it’s only a First Nations FSC fishery (food, social and ceremonial harvesting).

In addition to checking the local sampling programs, we observe the weather conditions in our area as well. If it’s cold, overcast and in the middle of winter, algae is not very likely to grow and cause an algae bloom, and thus the toxins that make bivalves harmful. However, if it’s near the start or the end of the harvesting season, it’s especially important to keep an eye on the weather and temperature, as the risk for biotoxins increases (this can also happen mid season as well – so always keep an eye on your weather apps!).

And to add another layer of safety on top of watching the local biotoxin sampling and the weather, you can also consult with elders in your family or community. Elders hold a wealth of knowledge on traditional harvesting, and can have years (often decades) of experience to draw from to determine safe harvesting conditions. They might even share one of their hot spots with you! Lol

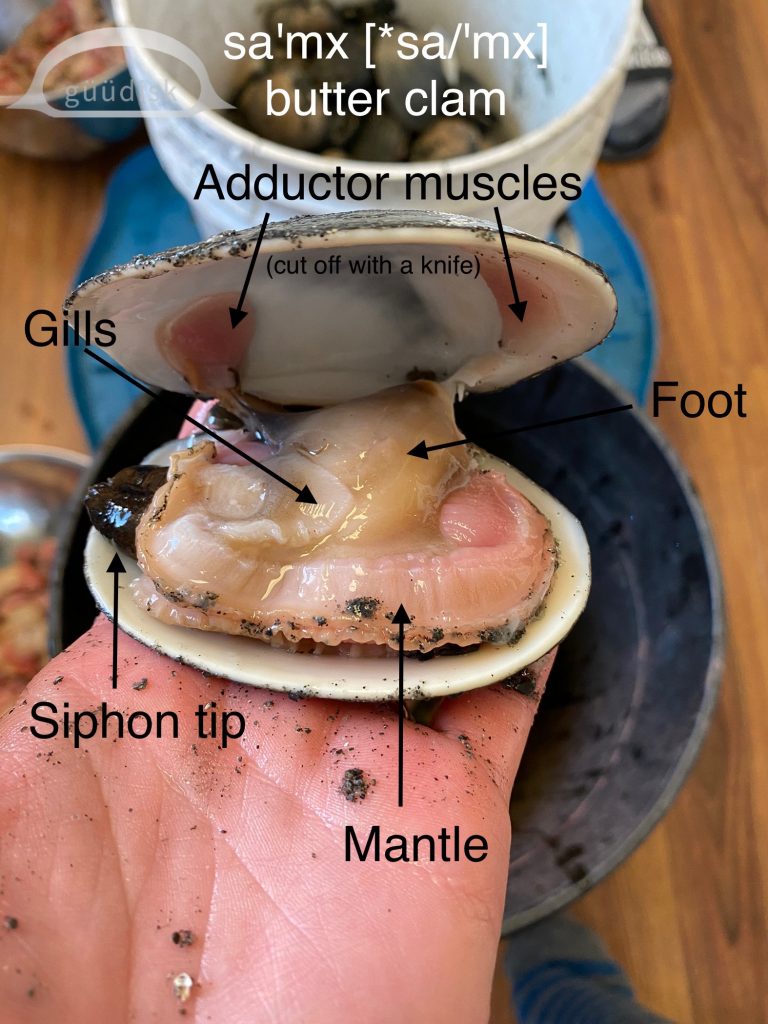

The siphon on the ts’a̱’a̱x can accumulate biotoxins, so we do not eat this part of the shellfish. The meat is the edible part of the clam, including the foot (the firm, muscular chunk of meat in the middle of the clam), the mantle (we call these the lips 👄 this is not the scientific name lol), and the adductor muscles (which we call the eyes 👀).

In our territory, there are a few different types of ts’a̱’a̱x, including sa’mx [*sa/’mx] – butter clam, Manila clams, and little necks. This blog post talks about sa’mx.

Cleaning sa’mx

1. First off, it’s good to rinse the sa’mx before you start shucking. We tried rinsing them at the boat when we finished harvesting, but only the top of the bucket got a good rinse lol we should have given these a hose down before we started shucking, but we were already on a roll. Steve says it’s better to keep the sand on the clams until it’s time to clean them, as it helps them to stay fresh for longer. If you leave the sand on them and store them in a cool place, they can last a few days in the bucket. But we usually clean them fairly quickly.

Then, save the clam meat for later! We usually eat them fresh, or vacuum seal and freeze for later. We also give them one last rinse in a strainer before we eat them, to get any last sand or gravel off them.

S&L – February 6, 2022